Warning: Retirees Will Pay for COVID-19 Crisis

How Safe Is Your Retirement Income From COVID-19 Crisis?

It will take years for experts to fully assess the impact of the coronavirus pandemic. But you don’t need a PhD in economics to predict one consequence of the outbreak: Uncle Sam will emerge from this crisis saddled with trillions of dollars in extra debt.

The Congressional Budget Office recently published a sobering report on the state of the nation’s finances. The agency estimates that the federal deficit will be almost $4.0 trillion in fiscal 2020. (Source: “CBO’s Current Projections of Output, Employment, and Interest Rates and a Preliminary Look at Federal Deficits for 2020 and 2021,” Congressional Budget Office, April 24, 2020.)

The current total debt is more than $26.0 trillion. For perspective, that equals more than $80,000 for every man, woman, and child living in the United States today. (Source: U.S. Debt Clock, last accessed July 14, 2020.)

And come the November election, most politicians will argue that running up the nation’s credit card is no big deal. Chances are most voters will agree. After all, 140 million people now collect direct deposits from the government of $1,200 a month. Almost half of Americans pay no income tax. Officials have suspended student loan payments. Never mind the extra payouts to unemployed workers and forgivable loans to businesses.

It’s astounding. And as Jeff Bezos found out after Amazon.com, Inc. (NASDAQ:AMZN) tried to cut temporary raises to its workers, you can’t easily take back what you generously gave. Once people get a taste of living on the government dole, it’s hard to wean them off.

So the question is, who will pay for all of these programs?

To quote Baron Mordo from Dr. Strange, “The bill comes due.” Officials have a variety of options to shore up the nation’s finances. Unfortunately, you might not like any of them.

Austerity represents the most obvious solution. Politicians can whittle down the debt through a combination of spending cuts and tax hikes. By ditching the national credit card, tightening our collective belts, and living within our means, the country can avoid a debt crisis in the future.

In theory, that will work. In reality, austerity amounts to career suicide to any politician.

Which taxes get raised? Which expenses get axed?

Nobody wants to see their precious program cut or their tax loophole closed. And as we saw during the 2009 financial crisis, nothing gets people out into the streets quite like tax hikes and spending hikes.

So it should come as no surprise that any political leader running on a four-year reelection cycle will skip this option. That leaves us with two less appealing alternatives, at least from the perspective of retirees.

First, the U.S. government can borrow a tactic from the playbook of developing countries: financial repression. This includes any measure to keep yields low or to prod investors to hold government bonds. By robbing savers of their retirement income, politicians can reduce the cost of financing their debts over time.

And this wouldn’t be the first occasion the U.S. government employed this tactic. During World War II, Uncle Sam ran up an enormous bill to fight back the Axis powers. Afterward, the Federal Reserve suppressed yields on government debt. Officials also kept a cap on interest rates that banks could pay to depositors and limited the private ownership of gold, thus discouraging investors from owning alternatives to Treasury bonds.

That strategy worked, according to a 2015 paper by the International Monetary Fund. The study found that, between 1945 and 1980, financial repression (along with inflation) lowered the country’s average interest expenditure by one to five percent of gross domestic product each year. (Source: “The Liquidation of Government Debt,” International Monetary Fund, last accessed July 14, 2020.)

In other words, trillions of dollars not paid out in retirement income to savers in the form of interest coupons.

The system “played an instrumental role in reducing or liquidating the massive stocks of debt accumulated during World War II,” explained the report’s authors, Carmen M. Reinhart and M. Belen Sbrancia. “We suggest that, once again, financial repression may be part of the toolkit deployed to cope with the most recent surge in public debt in advanced economies.” (Source: Ibid.)

And it appears the U.S. government wants to do exactly that this time around, too.

In March, the Federal Reserve announced a series of emergency measures and slashed their benchmark overnight lending rate to 0.25%. And since the start of the pandemic, the central bank has purchased about $3.0 trillion in government bonds in a bid to keep longer-term interest rates low. (Source: “Assets: Total Assets: Total Assets (Less Eliminations from Consolidation): Wednesday Level (WALCL),” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, last accessed July 14, 2020.)

Another approach would be to spur higher inflation.

Governments have long employed this strategy as a preferred way to repudiate their debts. We have seen it deployed as far back as ancient Rome, and more recently in places like Zimbabwe and Venezuela. By devaluing their country’s currency, politicians can pay back nominal debts incurred today with cheaper money in the future.

And the tactic could provide the same benefits to the United States. If officials can keep the inflation rate around three percent per year, that would wipe about $780.0 billion off the national debt annually. Maintain that policy over a decade or so and officials can whittle down the country’s liabilities to a much more manageable figure.

This policy, however, can devastate a society. Inflation rewards speculators and debtors, especially those people who like to live beyond their means. It also hammers the working poor, whose paychecks often fail to keep up with the rising prices of goods and services.

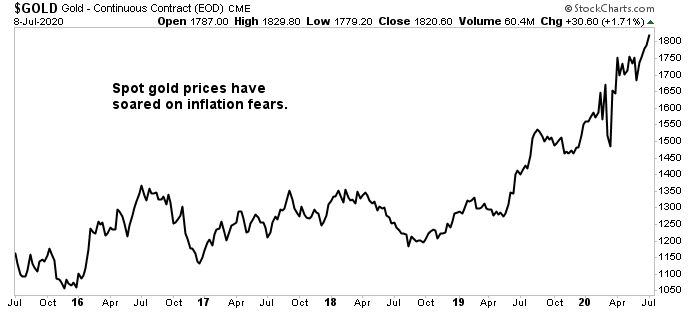

Chart courtesy of StockCharts.com

But it’s savers, as you might expect, who bear the brunt of this policy.

Each year, inflation chips away at the value of their nest eggs. Their losses don’t show up on a brokerage statement, but instead as higher prices for everything from bread and milk to heat and power.

“The arithmetic makes it plain that inflation is a far more devastating tax than anything that has been enacted by our legislatures,” wrote billionaire Warren Buffett in a famed 1977 Fortune op-ed. “The inflation tax has a fantastic ability to simply consume capital.” (Source: “Buffett: How Inflation Swindles the Equity Investor,” Fortune, last accessed July 14, 2020.)

To illustrate, say you have $1.0 million today for your retirement and the cost of living rises by three percent per year. In 10 years, your savings will only purchase $737,000 worth of goods. In 20 years, you will only be able to purchase $543,000 worth of goods. And what happens in 30 years? After three decades, your purchasing power drops to $401,000.

And this isn’t some theoretical scenario. In the 1970s, the U.S. employed an aggressive inflationary policy to fund its war effort in Vietnam. Over that decade, a dollar lost over half of its purchasing power. Those counting on pensions or fixed-income investments for their retirement income saw the value of their savings wiped out.

So how can you protect your retirement income?

I’ll leave that for another Income Investors column. As I’ve covered a number of times in recent weeks, you can always find winners during a crisis. Problem is, the list of losers right now is getting long.